By Steve Gunn

LocalSportsJournal.com

KENT CITY – David Ingles’ breakthrough season is just beginning.

For local basketball fans, that statement may sound odd. They know his Kent City boys basketball team recently ended its great season with a heartbreaking loss to North Muskegon in the Class C district finals.

It was the kind of season most coaches only dream of. The team posted the first 20-0 regular-season record in school history and won a conference championship, before losing the heartbreaker in districts.

Of course the incredible season meant a lot to Ingles. But it wasn’t his biggest accomplishment of the winter. Not even close.

His biggest triumph was something more important than anything that could ever happen on a basketball court.

He managed to break through a long, painful cycle of emotional isolation, brought on by years of severe back pain, an inability to work full-time, and general inactivity.

He was finally able to admit to himself that he was suffering from intense depression. He reached out and sought professional help after several frightening episodes, when he was haunted by thoughts of taking his own life.

Most importantly, he was finally able to open up to others about the battle he’d been fighting – and losing – on his own. He acknowledged his problem to his wife and family. He told his supervisors at the high school, and even the kids on his team.

And now he’s ready to tell anybody who cares to listen, in the hope that others may learn from his example, seek help, and avoid the kind of darkness he experienced.

People who know Ingles may be surprised to learn about his struggles. That’s because he’s always been an easygoing guy who knows how to put on a happy face.

But his world got very dark and scary at different points last fall.

One day last October, not long before the basketball season, he was out hunting by himself, when the desperate feelings overwhelmed him, more than any time before.

He found himself thinking about a permanent escape.

“Those dark thoughts just started coming in,” Ingles, 45, told Local Sports Journal. “I can’t work, I can’t help my family financially. It just kept piling on. I thought ‘There’s no way out of it, I’m better off not here.’ I was ready to be done.

“I was on my way to hunt, and I was thinking about ways to have an accident – not just hurting myself, but actually doing it.”

A few weeks later, he was home alone, and the dark thoughts came again. He knew he needed someone there with him, as quickly as possible.

“I texted Pam, asking her when she was going to be home,” Ingles said about his wife. “She answered and said about two minutes. I was done, I was in tears. I was just trembling.”

Pam Ingles remembers how she found her husband when she got home.

“That was the first time I saw that side of it,” she said. “I walked in, and he was sitting in the kitchen, which was not normal. He had his hoody up and he was just staring out the window.

“I got in front of him and asked him what’s wrong. He just broke down and said he couldn’t take it anymore.”

As it turned out, Ingles had written a second text message to his wife, after she answered the first one.

“After he calmed down, he showed me the other message on his phone,” Pam said. “It just said ‘Hurry.’ He never sent it.”

What would have happened if Pam had not been close to home, and he had been alone for another hour?

“I don’t know,” Ingles said. “I don’t want to speculate. I know I was in a bad spot.”

Intense pain and depression

If it hadn’t been for his physical problems, Ingles probably would have lived a pretty charmed life, working in schools, coaching basketball, and taking care of his family.

He grew up an active, happy, fun-loving guy who came from a basketball-crazy clan.

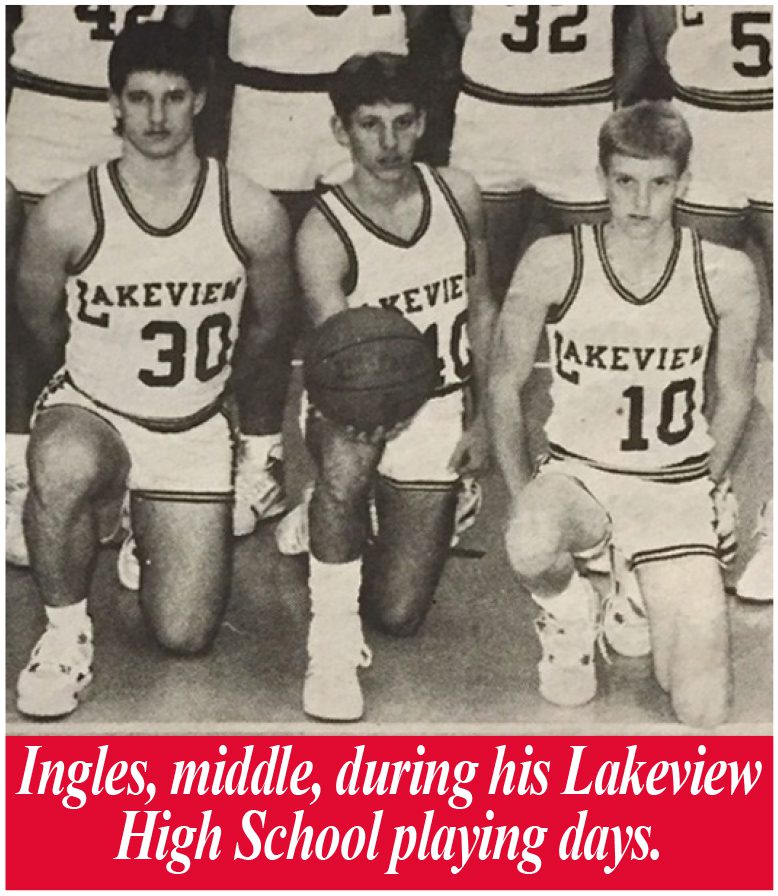

His father, Keith Ingles, was the longtime boys basketball coach at Montabella High School, and later Lansing Christian. Ingles literally grew up in a gym, and became a two-time All-State basketball player at Lakeview High School.

He earned an athletic scholarship to Cornerstone University, and played there for a year.

But after one season, back pain that had been creeping up for several years became more of a problem for Ingles. It finally reached the point where the physical demands of college athletics became too much.

“I had problems back in high school with my lower back,” Ingles said. “I heard that it may have been related to a birth defect or some other things, but nobody ever pinpointed the problem.

“I made it through my freshman season at Cornerstone, but I had to walk away from the team about three weeks into my sophomore season, back in 92.”

Ending his playing career was tough for Ingles, but there were other good things in his life. He met Pam between his freshman and sophomore years of college, and they were married in 1994.

And he didn’t have to leave the sport he loved.

He still played recreational basketball two or three times a week, which didn’t cause too much discomfort. And he started doing what he always wanted to do – coaching basketball, just like his dad.

That decision was par for the course, because coaching is definitely an Ingles family trait.

His uncle, Kent Ingles, is the coach at Big Rapids High School. His cousin, Jessica Haist, is the girls coach at Big Rapids. His brother Lee coaches at Cowan High School in Indiana. His brother Paul is a former assistant coach.

Ingles’ first coaching job was with the Big Rapids High School junior varsity team, while he was still in college.

After that he spent a year as an assistant coach at Alma College, two years as the varsity head coach at Whitmore Lake High School, one season as an assistant coach at Western Michigan University, and finally six years as varsity basketball coach, recreation director and aquatic center director at Allegan High School.

Finally Dave and Pam, who by then had daughter Marleigh, decided to move closer to home. Ingles took one year off from coaching while Pam secured a job as a preschool teacher in the Tri-County school district in Howard City.

Ingles went back to work and spent a year as the varsity basketball coach at Grand Rapids West Catholic, before he accepted a position as athletic director, basketball coach and dean of students at Muskegon Catholic Central in 2009.

The MCC years brought good times and bad times for Ingles. He spent three years coaching basketball, and his 2011-12 squad advanced all the way to the Class D state semifinals.

But the back pain started to intensify by the time he started at MCC. He finally went to a doctor and was told he had a bulging disk pinching nerves in his back.

“I would lock up at times, and I was stuck bending over and couldn’t move,” Ingles said.

He tried physical therapy, painful injections and various medications, but finally had to have major surgery in May of 2010.

The surgeons removed the bad disk from his spine and inserted rods and screws. They pronounced the procedure a success, but Ingles soon realized that wasn’t the case.

“It was a long time (after the surgery) before the pain was where I could handle it and go back to work,” he said. “I felt okay for about a year. It didn’t hurt as much. Then it was right back to the same old pain in my back and legs, and it kept getting worse.”

Suddenly he couldn’t do most of the things he took for granted in the past.

“After surgery, I couldn’t run, jump or lift more than a gallon of milk,” he said. “In the past when I needed stress relief, I would go play basketball or whatever, and that was taken away.

“At the father-daughter dances, I can’t pick Marleigh up and swing her. She looks at me and I can’t do it. It’s frustrating.”

By the end of the 2011-12 basketball season, when MCC made its run to the state final four, Ingles decided to give up coaching and concentrate on being the school’s athletic director.

But by the end of that summer, the intense pain forced him to leave MCC altogether.

Since then he has not been able to have a full-time job.

“It was hard,” he said. “I couldn’t do it. I could only sit for so long and stand for so long. I couldn’t make it through full days.

“By August, as we were getting ready for football season, the head of schools could see that I just wasn’t functioning. We had been talking about it for more than a year. I told him I was doing the best I could, but finally there was nothing I could do, and we parted ways.”

Ingles intended to take a year off from everything and try to heal. But basketball fever clicked in again as the new season approached, so he took the head coaching job at Reeths-Puffer when it was offered.

Ingles coached at R-P for three seasons, before he and Pam decided to move back to the Lakeview area, and he started looking for a nearby coaching job.

He accepted the Kent City position in 2015, but the house the Ingles had picked out suddenly became unavailable, so they stayed in their home near Ravenna, where they have lived since Dave’s MCC days.

Looking back now, Ingles believes depression started to creep into his life during his time at Muskegon Catholic. It was difficult to detect, because the pain caused by his back problems still dominated his thoughts.

“At Catholic you could see the pictures – my clothes weren’t fitting anymore,” he said. “I dropped from 180 to 150 just like that. I couldn’t eat and I wasn’t sleeping, and I didn’t know why.

“I had a parent come up to me and ask if I was okay. He noticed that I had lost a ton of weight quickly. I went to a doctor and he mentioned depression, but I didn’t really even understand what it was.”

The turning point

In his first two seasons at Kent City, Ingles’ basketball team did very well, posting a 14-7 record each year.

But personally, the dark days kept getting darker for the coach.

He wasn’t able to do much besides coach, work a few hours a day at a local golf course, and substitute teach on days when he felt up to it.

He started sitting around the house a lot while his wife worked and his daughter went to school. He missed working full-time. He missed playing basketball and doing other physical activities. He hated the fact that he couldn’t contribute much to the family income.

Ingles became sullen and withdrawn as depression overwhelmed his thought process.

“I started spending a lot of time by myself, with no TV, no lights, and it just got worse from there,” he said. “It took me awhile to realize that it was depression, and even when I realized what it was, I didn’t tell my wife.

“I would use my medication as an excuse. ‘I just took my meds, that’s why I’m sitting here by myself.’ That’s what I would tell her.

“Our house is basically a big circle, from the living room to the kitchen to the dining room. I would just walk that circle for hours.”

Pam noticed the growing problem, even though she didn’t fully understand what was happening.

“Over the years I picked up on his telltales,” said Pam, who originally attributed his moods to back pain. “I would come home from work and he would have his hoody up over his head while he was watching TV, and just tell me he wasn’t doing well. Trying to get him to talk during those times was really hard.

“It was affecting me, as well. I would be at work, wondering what he was doing and how he was doing. I was trying to keep up a show for our daughter, that everything’s okay.”

The situation reached a breaking point on that day last October, when Ingles went hunting and had thoughts about taking his own life.

He was alarmed by the fact that he was no longer frightened by the idea of suicide.

“It didn’t scare me anymore,” Ingles said. “When I first started thinking of that, I would push it aside. But I was ready to do it.

“I didn’t want to hurt anymore. I was tired of being alone. Any time any little thing happened – like some minor thing with the car – it became a huge thing to me. Everything just kept piling on.

“When I wasn’t afraid of it anymore, that’s when I knew I had to get help.”

Not long after that, Ingles stopped at his church in Kent City. He found his pastor, Ken Vanderwest, who was preparing to leave for a meeting.

Vanderwest, the father of one of Ingles’ players, cancelled his plans, listened to Ingles’ story, and helped him find a counselor.

Ingles started visiting the counselor and saw some light at the end of the tunnel. But there were still too many bad days, because he was still fighting his battle alone and shutting everyone out.

Even when he acknowledged his depression to Pam, he insisted they keep it to themselves, because he didn’t want anyone to know.

Then came that day last November when he was home alone, the dark thoughts came again, and he texted Pam in a panic.

At that point his wife decided she had to learn more about his condition, and become more involved in his treatment.

“We both went to see his counselor the next day,” she said.

Suddenly Ingles was no longer alone, and that made a very big difference.

“Going it alone was a hard battle,” he said. “I had a hard time explaining to Pam what I was going through. Then she came with me (to see the counselor) and I told her, ‘He can explain it better than I can,’ and he did. It was like a light clicking on for her.”

Opening up

The past few months have been better for Ingles.

He has continued to see his counselor, who is helping him accept the new realities of his life.

His back condition and the constant pain are permanent, as far as he knows. That means working full-time is no longer possible, most physical activity is still out of the question, and his income potential may be limited.

That doesn’t mean life, with his wife, daughter and great coaching career, is not worth living.

“This is the new reality I have, and it’s not all bad,” Ingles said. “I’m starting to see more positives.”

His basketball team’s 20-0 regular season also provided a big boost for Ingles.

The Eagles opened the season on a breathtaking note, beating Coopersville 50-49 in overtime, then just kept on winning.

There were some very close calls along the way, including a last-second 47-45 overtime victory over Morley-Stanwood in February to clinch the conference title.

The capper came in the last regular season game, when Kent City downed Grand River Prep 69-37 in a Senior Night home contest in front of a big crowd.

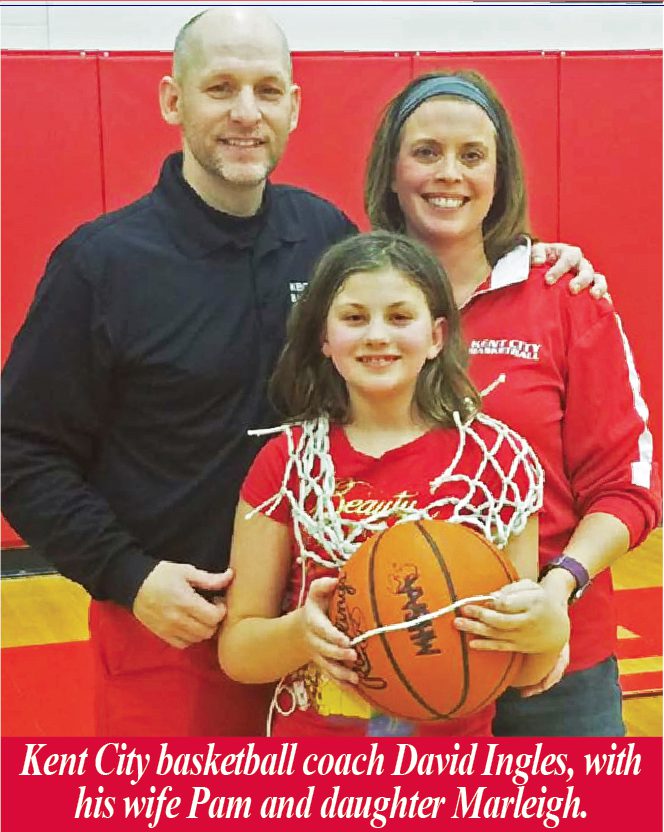

The team celebrated after the game by cutting down the nets in the Kent City gym.

Coaching has been physically challenging for Ingles, who has to keep a chair handy at practices, and relies on his assistants to do most of the physical work.

But the results have been invigorating.

“I remember I was on my way to the first practice of the season, and I called Pam and told her I didn’t know if I had the energy to do this,” said Ingles, whose team finished with a 21-1 record. “But once I got in there, the kids’ energy and enthusiasm helped me focus.

“They helped me more than I ever helped them. They are an incredible, unbelievable group of kids.”

But more than anything, Ingles is feeling more upbeat these days because he finally has allies in his battle with depression.

He’s on the same page as his wife, and they’ve told their daughter, now 10-years-old, about his challenges.

Meanwhile, his list of allies is growing exponentially, because he’s determined to keep opening up.

A few weeks ago, after the basketball team put the finishing touches on its perfect season, Ingles contacted Local Sports Journal and said he had a story to tell that went far beyond basketball.

He felt a need to share it with the public, because he knows there are frightened people out there battling depression alone, like he used to do.

“I kept it to myself and nobody knew, and all that does it take you to bad places,” Ingles said. “If I didn’t see a counselor, I don’t know where I would be right now. I did it too long on my own, seven years by myself.

“If one person reads this, says ‘That’s me,’ and gets counseling, it’s worth it. I may never know it. I don’t care.”

The impending publication of this story forced Ingles to reach out to family members and his professional circle.

Over the past few weeks, he and Pam have talked to Kent City High School Principal Bill Crane and Athletic Director Jason Vogel, explaining his condition and the challenges he’s facing.

Pam says she’s amazed and encouraged by her husband’s sudden openness.

“He went from one extreme in the fall, when he didn’t want anybody to know, to telling everybody,” she said. “That’s a huge transformation. This is a huge step for him.”

There was one other big step for Ingles to take before thousands of readers learned about his experience.

So he gathered his players together, just before districts, and told them everything he’s been dealing with.

“I think there was a little shock at first,” Ingles said. “It must be weird to see your coach break down. I practiced what I wanted to say all day, then I had a hard time getting started.

“But they were good, they were locked in, you could tell they were concerned. I told them I was okay, and I’m doing much better now.”

In addition to Muskegon County ‘s 24 hour crisis line at (231) 722-HELP (4357) (answered by a live credentialed clinician who can assist in developing a safety plan, refer to Mobile Crisis Services, and/or direct individuals to Emergency Services.), there is also a national crisis text line (send a text to 741-741), and a National Suicide Prevention Lifeline 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

We can all help prevent suicide. The Lifeline provides 24/7, free and confidential support for people in distress, prevention and crisis resources for you or your loved ones, and best practices for professionals.

Thanks for this article! It is truly courageous. Thank you Coach Ingles, you are an inspiration for our whole town of Kent City. Fantastic season! Go Eagles!!!!