By Steve Gunn

LocalSportsJournal.com

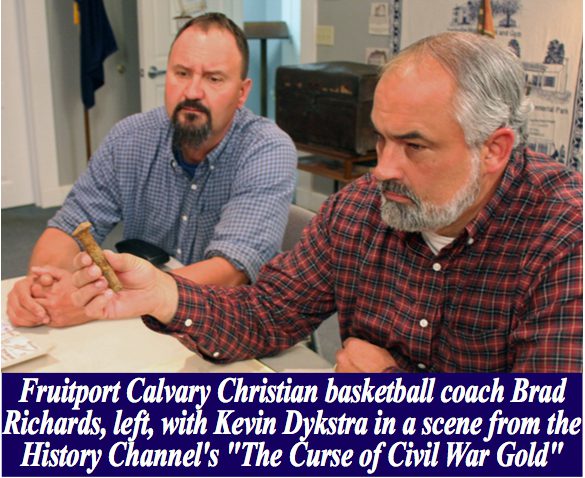

Brad Richards has two major passions, beyond his wife and children:

He has long been known, in the Muskegon area and beyond, for his success as a basketball coach.

He spent 12 years coaching girls and boys basketball at Ravenna High School, where he became the most successful girls coach in school history and was named the Associated Press state Coach of the Year in 2002.

For the past eight years he’s been the girls basketball coach at tiny Fruitport Calvary Christian, where his children are students.

His Calvary teams have been wildly successful, posting an overall 150-36 record. The Eagles have won the Alliance League championship for six years in a row, and Class D district titles for six of the past seven years.

But until recently, Richards’ enthusiasm for history was limited to teaching the subject at Ravenna High School, reading when he can find time, and checking out cool historic landmarks during family vacations.

“A few years back I took my family to Washington, D.C.,” Richards told Local Sports Journal. “If you ask my wife and kids, they will laugh and talk about how we stopped at and looked at every single monument in our nation’s capital.

“Another time we went to Gettysburg (Pennsylvania, the site of the famous Civil War battle). We have this old motor home, and we drove that across every inch of the battlefield and got out and looked at every single monument.”

But Richards’ historic endeavors became a lot more intense a few years ago, when he was approached by Kevin Dykstra, the facilities manager at Fruitport Calvary Christian.

Basketball practice had just finished for the day, and Richards was eager to head home.

“It was after practice, the day before a game, and he walked up to me and said ‘You’re a history teacher, right? I want to run something past you, and see what you think about it.’” Richards said. “I told him I only had five minutes, because I had things to do.”

Dykstra shared his theory about something related to one of Richards’ favorite historical subjects, the Civil War. It was also related to his hometown of Muskegon, which grabbed the coach’s interest even more.

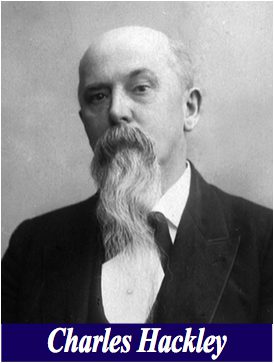

Dykstra said he believed the gold and silver reserve of the defeated Confederate government had found its way to West Michigan following the Civil War, and some of it may have ended up with 19th century Muskegon lumber baron Charles Hackley.

Hackley, of course, was a major philanthropist who played a large role in the development of downtown Muskegon.

So Dykstra talked and Richards listened, for far longer than he ever planned.

“After two hours of giving him five minutes, I was hooked,” Richards said.

“I’m a busy guy, with family and teaching and coaching, and I don’t have time for wild goose chases and silly stuff. But to have an opportunity to be part of an exciting discovery in our nation’s history is fascinating.”

What followed has become a new mini-career for Richards that’s making him a national cable television celebrity.

His contribution to Dykstra’s project started quietly. Richards spent hours digging through archives at the University of Michigan and Michigan State University, Hackley Library and the Torrent House in Muskegon, as well as the Library of Congress through online access.

“I was told details of Kevin’s theories, and I just dove in and tried to help the best I could,” he said.

Last winter Dykstra and Richards pulled all of their findings together and hosted three public presentations at Fruitport Calvary Christian school.

Dozens of local residents came to learn about the seemingly farfetched theory, and many left as believers.

“The first thing we did, we invited a small group only,” Richards said. “I wanted to do the same thing he did to me – tell them the story and see if they thought we were crazy. There were a few doctors, a military guy, an author, a college professor – a neat little slice of educated humanity.

“When we were done with that group, there was not a naysayer among them.”

The general public was invited to the next two presentations, and more people were similarly impressed, according to Richards.

“A lot of people showed up,” he said. “We had fun with it.”

Dykstra and Richards planned to continue their research and see where it led, regardless of whether their project attracted much public attention.

Then one day last spring, Dykstra told Richards that the History Channel was interested in creating a reality television series, based on their project.

A deal was soon struck, and Dykstra and Richards carried on their work. The only difference was that they suddenly had a television crew with them wherever they went, filming everything they did, to document their efforts, successes and failures.

The result is the new television series called “The Curse of Civil War Gold,” which premiered on the History Channel on March 6.

The six-episode series will air every Tuesday at 10 p.m. .

The idea for the TV show sprouted when Marty Lagina, a Michigan native and star of the hit History Channel show “The Curse of Oak Island,” heard about Dykstra’s theory and research.

“The way the whole thing came about, we were in New York with Marty when he told me he had been approached by someone who knew this guy named Kevin Dykstra,” said Joe Lessard of Prometheus Entertainment, which produces both “Oak Island” and “Civil War Gold.”

“I got in touch with Kevin Dykstra, and he shared his story with me and introduced me to Brad and the other guys he’s working with. We thought it was intriguing, so we shared it with our partners at the History Channel.

“We’ve spent the better part of the year working with them, following them with cameras as they’ve made a lot of great discoveries. The more we get into this, the more compelling the story is, and the more it’s worth pursuing.”

Suddenly Dykstra and Richards are reality television stars.

Richards admits he’s become something of a local celebrity since the show hit the air, particularly at Ravenna High School and around the town.

“High school kids don’t sugar-coat anything, and I hear the good and the bad (about the show),” Richards said with a chuckle. “During one of the first episodes I used the term ‘pow-pow,’ and now I can’t walk through the school library without hearing that one repeated.

“We went to a big hunting expo at Ravenna Baptist Church recently. There were like 500 people there on a Saturday night, and everybody wanted to say how much they loved the show, one after another. It was kind of overwhelming.

“All of the reaction has been pretty humbling. People are so kind and positive about it.”

Rebel gold in Muskegon?

Dykstra’s theory about the confederate gold starts with a few confirmed facts:

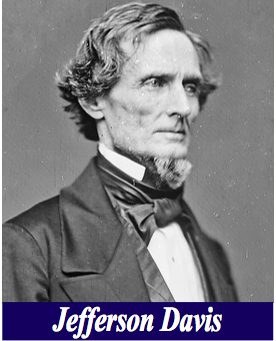

At the end of the Civil War, Jefferson Davis, the president of the defeated Confederate States of America, was fleeing the conquered capital of Richmond, Virginia, trying to avoid capture by the victorious Union army.

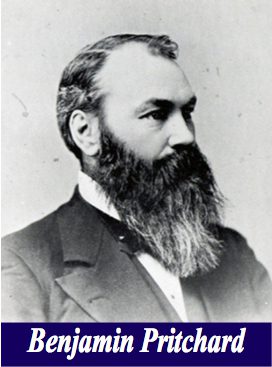

He was intercepted and arrested by the Michigan 4th Calvary, commanded by Lt. Col. Benjamin Pritchard of Allegan County.

U.S. government documents from the time claimed that Davis was traveling with about $10 million worth of gold and silver that belonged to the confederate government. It would be worth about $142 million today.

A lot of other historic tidbits led Dykstra to develop and pursue his theory, according to a recent story published by the statewide MLive news network.

While some claim that Davis did not have the gold with him, records show that he was captured with eight wagons and as many as 30 mules. Experts say eight wagons would have only needed 16 wagons.

Dykstra believes other wagons, with the gold and silver, were hidden in the nearby woods when Davis was captured.

Dykstra came across an old telegram, sent from Pritchard to an assistant of U.S. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton following Davis’ capture, stating “I returned to the site last night.”

Pritchard’s immediate commander, Gen. Robert H.G. Minty, had a son, Robert H. Minty, who grew up in Muskegon. He and some relatives had strong connections with Hackley National Bank.

Charles Hackley was a director of the bank, and later served as its president. Pritchard, meanwhile, established the First National Bank of Allegan in 1871.

Both banks printed an unusual amount of paper currency, which means they must have sent an unusual amount of gold to the U.S. Treasury.

Hackley’s net worth was recorded at about $10 million at the time of his death in 1905. But an authorized biography, published years later, claimed his lifetime earnings were about $3 million.

The biography says that Hackley made $372,000 in one day in 1972, about the time that Dykstra believes that the confederate gold was being quietly transported north by rail.

Finally, an old Lake Michigan lighthouse keeper supposedly made a deathbed confession in 1911 about a boxcar full of Confederate gold that was purposefully dumped into Lake Michigan near Frankfort in the 1890s.

The story of that confession was passed on to a man named Fredrick Monroe in the 1970s, and Monroe shared it with Dykstra.

Dykstra believes that boxcar may be full of some of the Confederate gold.

The television series adds a new twist to Dykstra and Richards’ work.

Their challenge is to find enough evidence to convince Lagina, the Oak Island star, to help arrange financing for an expensive underwater expedition to search for the boxcar full of gold in Lake Michigan.

“The sonar scanning of an estimated one hundred square miles will involve tens of thousands of dollars and Dykstra will need to show tangible proof of his theory to Marty before the Traverse City businessman will invest in Kevin’s operation,” said a press release from the History Channel.

“This leads Dykstra and his team on a compelling hunt to the scene of the original heist; into bank vaults to search for secret tunnels constructed to help launder the loot; and ultimately to the bottom of Lake Michigan to finally decipher one of the biggest conspiracies in American history.”

By the end of one recent episode, Dykstra, Richards and their crew came across an old confederate silver coin near the site where Davis was apprehended in Georgia, as well as parts of old wagons dating back to the Civil War period.

The show ended with Dykstra on the phone with Lagina, telling him about those latest discoveries. Lagina said he was somewhat impressed, and told them to keep searching and digging for more clues.

The rest is to be continued.

While viewers wait in suspense to see what happens next, Richards is finally back home, after months of traveling to film the series.

He admits that all the travel, and being away from home and his teaching job at Ravenna High School, was challenging.

“It’s taken a lot of time,” said Richards, who declined to say whether he was paid for his work on the TV show, or whether it will have a second season. “I’m just grateful for my wife and family’s understanding and support.

“I’m also grateful to the people at Ravenna Public Schools. I couldn’t have done it without their gracious understanding, which allowed me to take time off from work.

“We traveled a lot of miles, and I’ve spent a lot of time away from my family. For me that was the hardest part. But it’s been an exciting adventure, too.

“Through a lot of the summer and fall, we just continued our quest to get to the bottom of the mystery. Show or no show, we were going to keep doing what we do. They (the production crew) just kept following us.”

Back home to basketball

Unfortunately for Richards, his television travels kept him on the road late last fall as his Fruitport Calvary Christian girls basketball team started practicing for the new season.

In previous years, that wouldn’t have been such a big deal, because the Calvary girls always seemed to have plenty of talent and experience.

That was particularly true in 2016-17, when the Eagles had four seniors in the starting lineup, and set a new school record with 22 victories.

But those seniors graduated, and the 2017-18 Eagles were very young and inexperienced. There were no seniors on the team, and the starting lineup included three juniors and two sophomores.

Richards very much wanted to be in the gym to help the young players get ready for the season. But he ended up missing most of the preseason practices, as well as two scrimmages.

Richards said his two veteran assistants, Dan Hamilton and Jim Warren, did a great job of preparing the team as much as possible for the season.

Even so, he was still worried that the young Eagles might be in for a rough ride as they dove into their schedule.

“It was very difficult to be apart from the team,” said Richards, who played basketball at Western Michigan Christian High School, Muskegon Community College and Cornerstone University.

“I was getting video clips sent to me, but it wasn’t the same. I guess you can’t be in two locations at one time when you’re human.

“Dan Hamilton and Jim Warren are top-notch coaches and even better people. When I got back, I was impressed with where the kids were at.

“But we still had a realistic meeting, and I remember saying, ‘Look, we can’t get depressed when we lose some games this season, because we’re going to lose some games.'”

That turned out to be the case, at least at first, when the Eagles lost their first two games, to Muskegon Heights and Mason County Central.

For Richards, that’s not the norm, and he was concerned about his team.

He found himself on the phone a few times with his two oldest daughters – Taylor and Allyson – who both starred at Calvary and now play basketball for Cornerstone University.

“I remember telling them that I wasn’t sure if we were going to win a game,” he said. “Once daughters get to be that age, they are more like friends and supporters. They just told me to hang in there. And then, man, all of the sudden this team took off.”

After the two opening losses, the Calvary girls won four games in a row, lost one, then ripped off 16 consecutive victories.

In the process they secured conference and district championships, and won their first game in regionals.

The team was led by sophomore Kelsey Richards (the coach’s youngest daughter), who averaged 26 points per game; sophomore Lizzie Cammenga, who averaged 13 points; and junior Brionna Johnson, who averaged 15 rebounds.

The Eagles’ district title came in exciting fashion, when Cammenga hit a layup at the final buzzer to give Calvary a 44-42 win over Muskegon Heights.

“We told the girls two things – number one, rely on the fact that God has a plan for your life and our team, and number two, when you get knocked down, get back up and keep fighting,” said Richards, whose team finished 20-4.

Unfortunately the end of the season was all too familiar for the Eagles.

They met up with perennial state power Mount Pleasant Sacred Heart in the Class D regional finals. Sacred Heart had beaten Calvary in regionals in each of the four preview seasons.

Calvary tried a new tactic this year by slowing the game down, and led 12-11 at halftime, but eventually fell 37-20.

“The first couple of years (of losing to Sacred Heart), we felt kind of sorry for ourselves,” Richards said. “Every year they’re ranked No. 1 or No. 2 in the state.

“But look, you try to bloom where you’re planted. Hope springs eternal. Maybe next year we’ll get a chance to play them again.”

The Pritchard House, The Stairway that he built himself. Could he have hid the gold there?

Have you traced the families of the other men that were in the same company in the Civil War to find if they had similar stories?

Have you guys looked into the Mumford plantation in Ga rumors have that one of Jefferson soldiers made a side trip and brought Mr. Mumford gold to keep safe just something interesting to look into

MI also has a supposed connection to the KGC with Jesse James, through his mother whom he visited here. There was a one-armed school teacher in Higbee, an old community between Morley and Stanwood who was rumored to be Mrs. James, and she is buried in an old cementery north of the Higbee church. Talk was that she helped the KGC who visited her and there may still be old mason jars filled with gold coins in the area. I love the old stories and especially ones tied to Civil War connections because of my great grandmother being one of the last CW widows in MI when she passed in 1972!

Richards, as a history teacher, should not be believing some of the phony ideas these guys are being fed. Stanton hated the south and would not have had anything to do with Booth. And Booth died in that barn the same as Hitler died in Berlin. Just a bunch of fantasy theories. Again, a school janitor might believe it but Richards should know better